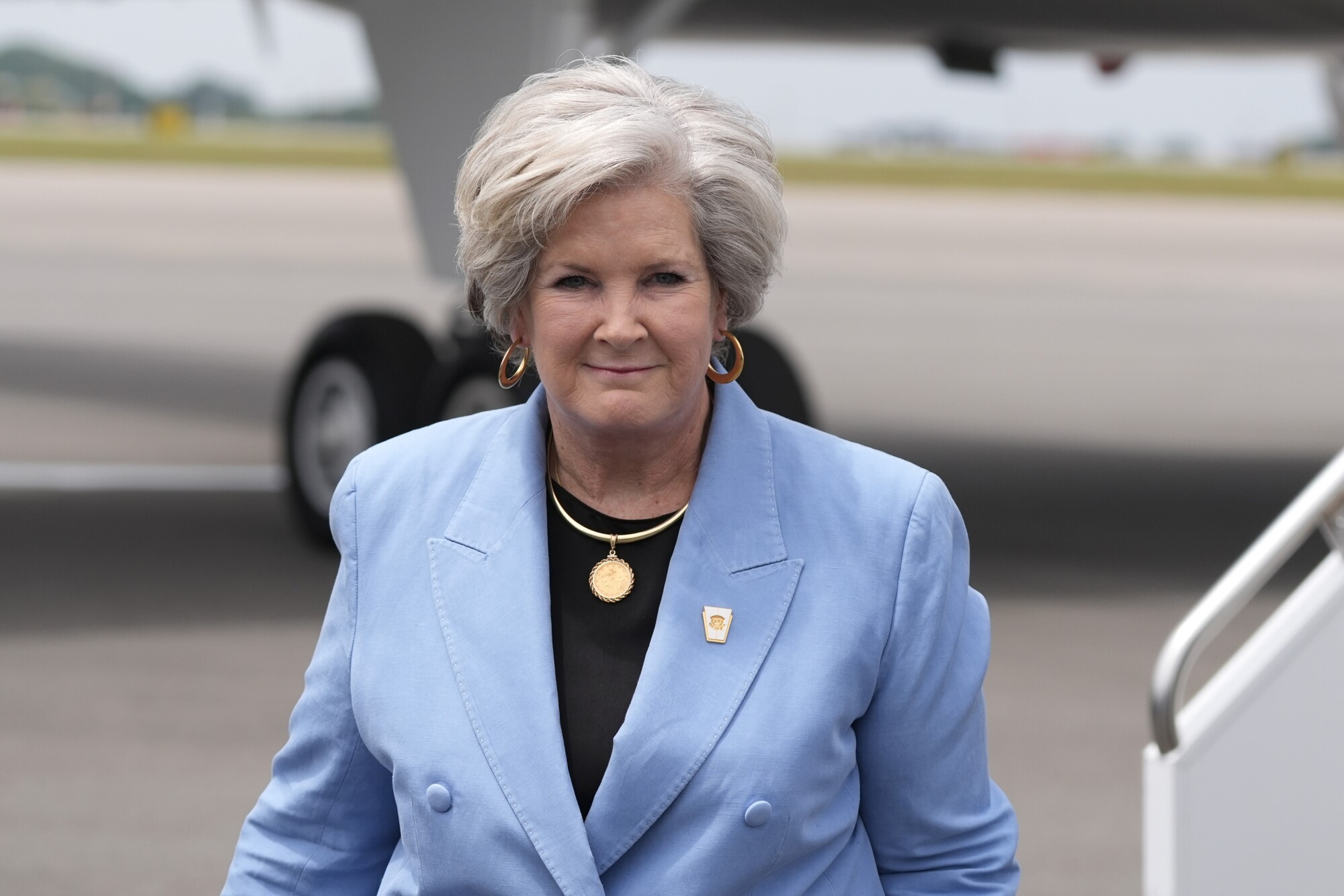

Alice Marie Johnson was set to bring her latest list of pardon recommendations to President Donald Trump in a meeting just before Christmas last year, an exclamation point at the end of a year marked by the reemergence of a muscular pardoning operation at the White House.

But the meeting between the president and Johnson, his “pardon czar,” was cancelled, joining a list of several planned meetings with people in charge of presenting pardons that were ultimately pulled off Trump’s schedule in late 2025, according to multiple sources familiar with the White House’s pardon process.

Senior leadership, including White House chief of staff Susie Wiles, had grown concerned about the optics of the president’s pardons, according to three people familiar with discussions, and moved to tighten the process. The effect of those efforts limited Johnson’s access to the one person who makes the final decision: Trump.

“It’s not just that she needs to see the president, but the president needs to see her,” said Peter Ticktin, Trump’s former lawyer who has advocated for pardoning Jan. 6 rioters and members of the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys, told NOTUS. “It’s not like Donald Trump doesn’t want to pardon people.”

Johnson’s time in the dark was temporary, befitting a White House where influence ebbs and flows. She was seen at Mar-a-Lago on New Year’s Eve and had a brief conversation with the president, according to two of the sources. About two weeks later, Johnson, a Black, 70-year-old grandmother who received her own pardon from Trump during his first term, got clemency for at least four people from her recommendation list for the first time in months. It was the largest number of pardons since May for people who had been convicted of federal crimes. And last week, in a sign the clemency doors are widening again, Johnson posted a picture of herself inside the West Wing holding a signed pardon for one of five former professional football players with crimes ranging from drug convictions to perjury.

More than a year in, the White House’s pardon process remains a puzzle for those trying to navigate, and in some cases profit, from it. The nearly dozen people who NOTUS spoke with — including sources both outside the Trump administration, like lawyers and lobbyists, and inside the White House — described an ever-changing situation. Many said it is predicated on who has access and who can create the most appealing stories for their clients.

“There is no process, there is no right way to do this,” another source involved in the pardon process said. “It’s chaos.”

White House officials say it’s all a part of the robust process to ensure pardons are being handed out ethically. “It may seem chaotic, but there’s a defined process in place,” a senior White House official told NOTUS.

“There has been no change to the pardon process,” another White House official told NOTUS, denying Johnson had been even temporarily limited and chalking up any canceled meetings to the unpredictability of the president’s schedule. “The Administration has always had a robust review process which involves the Department of Justice, Alice Johnson, and the White House Counsel’s office. Ultimately President Trump is the final decider. Susie is simply ensuring the process, which has always existed, is followed.”

Multiple people NOTUS spoke with have tied the White House’s efforts to tighten control over pardons to Johnson’s decreased access. There’ve been concerns internally over the outside reaction to some of the pardons. Senior aides, including Wiles, have been concerned with how people are profiting off the process, according to two sources familiar with discussions on pardons.

Administration aides have even gone so far as to pull some potential pardons from being approved after officials found that someone would directly profit from them, according to a source with knowledge of the pardon operations.

The president has no set time on his schedule every month to review clemency recommendations from his team, according to the senior White House official. And there is no set number of pardons that the administration ultimately wants to achieve. There are almost a dozen people within the White House who are working on pardons at any time.

While those close to Trump believe he’s committed to pardoning more people than his predecessors did, and at a more regular rate, some have been disappointed by his stop-and-start attention to clemency and by the cases that have dominated the news, especially those concerning high-profile fraud.

“If you elevate someone to a role like pardon czar and create a new pardon office, you should use it to carry out your goals,” a Republican operative with knowledge of the pardon operation said.

But for as much as the public and private outcry over the scope of his pardons has occasionally concerned his staff, Trump continues to flex his constitutionally enshrined power in a way that other modern presidents haven’t.

“At this point, Trump really doesn’t give a shit about public reactions to his pardons,” according to a source familiar with Trump’s approach during this administration. The person said that Trump has, in at least one instance, told an ally that they should ask for a pardon for a client navigating the justice system.

To date, the president has granted clemency to around 1,700 people since the beginning of his second administration. The process has been largely moved to the White House, as NOTUS has previously reported, instead of operating solely out of the Department of Justice’s pardon office. Trump has issued pardons unpredictably, granting clemency for a single person (as opposed to a group of people) repeatedly, as well as issuing blanket pardons for allies not even convicted of federal crimes.

But the pace, even excepting the 1,500 people who received pardons or commutations for their actions at the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, has eclipsed that of Trump’s most recent predecessors for pardons issued in the first year of his second term.

“I think that pardons haven’t been given the same priority that they were given at the end of the last term. And that’s natural,” said one person who is actively consulting other lawyers and lobbyists on pardon strategy. “I mean, most presidents wait to the end of the last term to do their best pardons anyway.”

Two sources familiar with White House’s plans said that the biggest hurdle to getting pardons across the president’s desk was finding time in his schedule. Though Wiles ultimately decides who can get into the Oval Office to see Trump, there are a host of people who lawyers or lobbyists seeking pardons for their clients have to get through first. A third source described a dynamic where power is frequently shifting between White House aides, making it imperative for advocates to maintain some form of relationship with as many people inside the operation as possible.

Johnson has been a go-to for many with clients looking to get their case heard. Criminal-justice advocates celebrated when Trump appointed her as his pardon czar. They viewed her as a serious person with a deep understanding of the system and a true commitment to its reform, especially given that she was incarcerated herself for more than two decades and pardoned by the president.

She has advocated for people incarcerated for drug offenses, celebrities and people charged with fraud and other white-collar crimes, and she’s championed the president’s belief that the justice system has been politically weaponized. Johnson told NOTUS in an interview last June that she personally presented cases for the president to review in the Oval Office, along with Wiles and White House counsel David Warrington. “It has to be clearly laid out to him,” she told NOTUS of the process. “I’ll take the lead, [Warrington] and myself on explaining the cases, really explaining every aspect.”

But Johnson’s access to Trump has been limited in recent months, four sources with knowledge of the White House’s operation told NOTUS. Multiple planned meetings to present cases were called off. Last year, Johnson requested to become a special government employee, which means she can serve only 130 days out of a calendar year and can profit from business outside of the government.

The White House defended Johnson, saying she meets regularly with the president’s staff and the president himself on pardon recommendations.

“Alice Johnson is the perfect person to be pardon czar and works alongside [Office of Legal Counsel] and [White House Counsel] to put forth pardon recommendations to the President. Alice regularly meets with WH officials and the President on pardon recommendations,” the official said.

Having consistent, direct access to Trump on clemency can make for extremely lucrative business. Sources involved in the pardon process outside the White House have told NOTUS that they’ve been offered millions of dollars to try to get a pardon for someone, and have heard of others taking an exuberant amount of money from those convicted or charged without ever advocating on behalf of them.

Moderating who gets to have that kind of sway has proved challenging.

“Susie Wiles is doing a great job,” said Ticktin, who believes that there are likely thousands of people deserving of pardons because of the various ways the federal government has weaponized the criminal-justice system. “There’s a lot of people that think that she has a different agenda, because they don’t understand her position … She’s a gatekeeper, OK? So who does she have to keep away from the president? She has to keep people [away] that are wasting the president’s time.”

There have been significant stretches of time where very few pardons have been granted. Between the beginning of June and the end of October of last year, the president only granted new clemency to two people; one convicted of wire fraud and the other of violating money-laundering laws.

The president has granted clemency to more than two-dozen people who have been accused of, convicted of or pleaded guilty to white-collar crimes. That includes David Gentile, a former private-equity executive who was sentenced to seven years in prison for defrauding thousands of investors to the tune of $1.6 billion. With Trump’s commutation, he will no longer be required to pay more than $15 million in restitution. It’s still unclear who advocated on Gentile’s behalf, but critics viewed the clemency as another signal that the White House would not take corruption among elites seriously.

Another act of clemency that even had some of the president’s allies scratching their heads was the pardon of the former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, who was sentenced to 45 years in prison for multiple drug-trafficking and weapons charges. Roger Stone, Trump’s longtime ally, sent the president a letter written by Hernández seeking clemency, two sources told NOTUS. The letter cast Hernández as a victim of the Biden administration, a frequent claim used by pardon seekers to attract Trump’s attention.

Senior officials, NOTUS previously reported, temporarily slowed the pardon process down, which led to the four-month hiatus of the president approving pardons. Part of the concern was over the optics of who might be profiting from the pardon industry.

“It’s not just [Susie] that’s concerned,” one source familiar with White House leadership’s thinking told NOTUS, noting that past administrations have been concerned about the optics of their own pardons. “Everyone has had this concern.”

Others say that while Johnson has successfully gotten people pardoned, her role, along with the DOJ’s pardon attorney, is more peripheral relative to those in the White House counsel’s office like Sean Hayes, who once worked for Rep. Jim Jordan of Ohio, or Warrington, who leads the office.

“It seems like Sean Hayes is the gatekeeper for Dave Warrington, who is the gatekeeper for Susie Wiles,” said one person with knowledge of the pardon process, who added that a pardon is unlikely to happen “if it doesn’t ever get to Dave and Sean Hayes.”

Though that isn’t the only way. Alternative routes include going through Trump’s children, the person said.

Ed Martin, the Department of Justice’s pardon attorney, has also had some of his powers reduced, according to two people familiar. One person said he was layered by Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, reducing his role in pardons largely to paperwork. Other outlets have reported that he was also moved out of the main DOJ headquarters and might be leaving the department all together. In recent days, Martin has worked to downplay any friction between Blanche and himself, and has been seen repeatedly at the White House.

There are multiple high-profile people seeking clemency at the moment, according to self-admissions and documentation. The rapper Fetty Wap, whose legal name is Willie Junior Maxwell II, is seeking a pardon after he was released early due to the First Step Act program, passed in the president’s first term. Maxwell was released to home confinement in December, limiting his ability to travel as an entertainer.

“Mr. Maxwell’s post-conviction pardon request reflects his desire to formally and fully close this chapter of his life, restore his civil standing, and continue rebuilding personally and professionally,” Abesi Manyando, Maxwell’s spokesperson, said in a statement to NOTUS. “While he has taken responsibility for his past actions and successfully completed his sentence, a pardon would allow him to move forward without the lasting barriers that often accompany a conviction.”

Ryan Salame, the former CEO of FTX Digital Markets and a Republican megadonor, made clear on X that he was seeking presidential reprieve, writing, “If I am granted clemency I promise to spend the remainder of my sentence working as an ICE agent.” Salame was sentenced to 90 months in prison after pleading guilty in 2024 to campaign-finance violations and a cryptocurrency fraud scheme.

But there’s a new hitch regarding clemency for famous or well-known people who don’t have a long and proven pro-Trump record, two people with knowledge of the White House’s process said. Trump is still smarting over his pardon of Rep. Henry Cuellar, a Democrat who is running for reelection as a Democrat in Texas. The president has since blasted Cuellar for a “lack of loyalty.”

The third source said there have been rumors that the White House will not be prioritizing drug offenders in federal custody or those involved in crypto cases, after the president pardoned several in the digital-currency sector and cut a deal with “Bitcoin Jesus” Roger Ver.

Fundamentally, those involved say it’s both access to the president and how the case is framed that make for a successful pardon. A common theme among those pardoned in Trump’s first term was that many of them incurred a trial penalty, one person told NOTUS — they took their cases to trial and ended up with stiffer punishments than if they had pled to lesser charges. This time around, pardons have gone to those the White House believes have had the justice system weaponized against them.

“If your client was sentenced by Judge Boasberg, well, Trump hates Boasberg, so he’s going to give him the finger, right? … Or this prosecutor is the same prosecutor who OK’d the search warrant of Mar-a-Lago. Well, fuck that guy, right?” one person with knowledge of the pardon process said. “It’s, what is the language that the president’s going to care about?”

Sign in

Log into your free account with your email. Don’t have one?

Check your email for a one-time code.

We sent a 4-digit code to . Enter the pin to confirm your account.

New code will be available in 1:00

Let’s try this again.

We encountered an error with the passcode sent to . Please reenter your email.