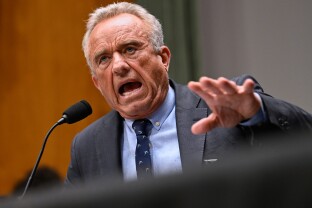

The Department of Health and Human Services paid $150,000 to an Arizona law firm for its expertise on the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program — an indication that the department could be readying changes to the VICP, which HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has criticized in the past.

The award made last month went to the firm Brueckner Spitler Shelts without specifying an individual recipient. But one lawyer at the firm, Andrew “Drew” Downing, is known nationally for his work litigating claims of vaccine injuries. Downing has also been involved in lawsuits against vaccine manufacturers claiming they downplayed the risks of severe side effects.

He has a track record of making both valid criticisms of the program’s shortcomings as well as dubious claims about the safety and efficacy of the Gardasil HPV vaccine.

While Kennedy hasn’t spoken publicly about wanting to make changes to VICP since becoming health secretary earlier this year, but in a 2022 post on X Kennedy said the current vaccine compensation system “protects government agencies and corporations, not vaccine-injured children.”

Three lawyers actively litigating cases before the VICP told NOTUS that nothing about the program has changed since Kennedy took office. But public health experts have theorized that it may be a target of the Make America Healthy Again movement due to the important role it plays in determining who gets compensated for vaccine injuries, what counts as an injury, and who — if anyone — is to blame.

HHS did not respond to a request for comment about Downing’s role at the department or any planned changes to the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program.

Downing could be a helpful partner for Kennedy if he does decide to make changes to VICP: An established lawyer who’s represented clients claiming to have suffered a wide range of vaccine injuries, he was one of the litigators on a case against the pharmaceutical company Merck where multiple plaintiffs accused the company of downplaying the risk of the HPV vaccine Gardasil causing certain severe side effects, like Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome and Primary Ovarian Insufficiency .

A federal judge ruled in favor of Merck in April, stating that the FDA has rejected the notion that Gardasil can cause the health issues the plaintiffs experienced.

But in a 2023 podcast episode with Children’s Health Defense, the anti-vaccine organization once led by Kennedy, Downing claimed that Gardasil only protects against “very few strains” of the HPV virus and hypothesized that the vaccine can actually cause cervical cancer instead of preventing it. Studies have shown that the HPV vaccine can reduce the risk of cervical cancer by up to 90%.

Downing told the podcast hosts, “Gardasil was marketed, early on, as a cure for cervical cancer, and it’s not.” He also said he believes there is “massive, massive underreporting” of injuries caused by Gardasil. (While researchers believe vaccine injuries often go unreported, studies show that severe injuries are reported more often than milder ones.)

Downing didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment on his role at HHS.

A surge of claims in the 1980s against companies making the DPT vaccine caused most manufacturers to stop making the shots altogether — until Congress stepped in and passed the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act in 1986, which established the VICP. Once vaccines are added to the VICP, a 75-cent tax on every shot goes to the program’s compensation fund. Patients who have suffered serious health issues as a result of getting a vaccine can file claims for loss of wages, medical bills, and pain and suffering. Pain and suffering claims are capped at $250,000.

To the MAHA movement’s dismay, these claims are considered no-fault, meaning that manufacturers aren’t held liable for any injuries caused by the vaccines they produce. Public health officials argue that the program is critical for encouraging pharmaceutical companies to continue producing vaccines.

Vaccine policy has recently come under close scrutiny from HHS leadership. Last week HHS fired all 17 members of the committee that makes vaccine schedule recommendations for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — replacing a slate of them with some vaccine-skeptical members — and Kennedy announced last month that the CDC would no longer recommend COVID-19 booster shots to healthy pregnant women or children.

The VICP isn’t without room for improvement: With only eight “special masters” overseeing claims, it can take years for plaintiffs’ cases to be heard. The pain and suffering compensation limit has never been adjusted for inflation. And since immunizations can generally only be added to VICP by HHS after Congress passes an excise tax on the shot, some vaccines, including the COVID-19 shots, still aren’t included in the program — meaning anyone who believes they’ve been injured by a COVID-19 vaccine can only file in a secondary program that further limits the awards plaintiffs can receive.

Altom Maglio, a vaccine injury lawyer who serves as co-chair of the American Association for Justice Vaccine Injury Litigation Group, said an important change HHS could make to the VICP would be adding COVID-19 to the list of covered vaccines, something that’s supposed to happen two years after the vaccines are introduced to the market.

“We are not doing right by the people who had what they were supposed to do — got vaccinated — and had very unfortunate adverse reactions,” said Maglio.

Vaccine injury lawyer Isaiah Kalinowski said the VICP’s issues should be addressed since those injured by a vaccine have few opportunities for recourse other than the federal compensation program: By design, the law makes it extremely difficult to sue vaccine manufacturers directly.

“If you’re going to make everyone jump in one boat, you better make sure that boat isn’t leaking,” said Kalinowski.

Bills that would increase the number of “special masters” and the pain and suffering compensation limit have been repeatedly introduced by lawmakers, most recently in 2023, but have never passed.

But Kalinowski added that he felt addressing the VICP’s compensation and personnel limitations would, by and large, solve its problems. Kennedy and other members of the MAHA movement have harshly criticized the system for reasons beyond what most public health officials feel is reasonable, including pushing for vaccine manufacturers to lose the legal shield VICP provides.

Any adjustment to VICP’s legal jurisdiction would require an act of Congress. Still, Kennedy has other options for altering the program: Some of the MAHA movement’s criticisms center around the idea that the table of covered injuries, which is maintained by HHS, doesn’t include injuries that they believe vaccines can cause.

Downing has also criticized the injury table. In the 2023 Children’s Health Defense podcast episode, Downing said VICP has been “overly restrictive” with what it considers a vaccine injury since the 1990s.

“It’s very difficult to win a case once the government deems it off the table,” Downing said. He cited plaintiffs who have brought claims of health issues like cervical cancer or primary ovarian insufficiency that have limited evidence to support the idea that they can be caused by vaccines.

Downing also spoke with frustration about the VICP not compensating petitioners because their health issues occurred slightly too long after they received a vaccine for the program to consider it caused by the immunization, or who brought claims after the three-year statute of limitations.

Downing has litigated dozens of vaccine injury cases before the VICP as recently as this month.

Many of the cases he’s worked on have resulted in compensation for plaintiffs because they met what the VICP’s regulations consider an injury likely to have been caused by a vaccine — that it was an issue that scientific studies have shown can be caused by immunizations in rare cases, and that it occurred soon after the vaccine was administered. While vaccines are well-tested and considered overwhelmingly safe, there is still the rare risk of serious side effects like Guillain-Barré syndrome, where the immune system attacks the nervous system.

Some of the cases he’s worked on, like the suit against Merck claiming that it downplayed Gardasil side effects, were not brought to litigation through the VICP. That was a civil suit — an important distinction because the VICP doesn’t require plaintiffs to actually prove the vaccine manufacturer was at fault, just that the petitioner suffered an injury caused by a vaccine.

Renée Gentry, director of the Vaccine Injury Litigation Clinic at George Washington University Law School, said she doesn’t do civil litigation for vaccine injury cases.

“If you think it’s difficult going up against the federal government, try Merck,” Gentry said.

But Gentry added that she felt that HHS and the Department of Justice, which argues vaccine injury cases on the government’s behalf, had become more willing to go to bat for vaccines in recent years — arguing against petitioners’ claims that would have previously been seen as straightforward.

Gentry said bringing VICP back to its original goal of quickly and painlessly compensating people whose injuries were likely caused by vaccines would require a “culture shift” at HHS and the Department of Justice.

“Which I think we may have now,” Gentry said.

Both Gentry and Kalinowski said they believe Downing has a deep understanding of the VICP — and its limitations.

Kalinowski said he felt that Downing would push for changes to the VICP if given the opportunity: “If he’s able to do anything, it’s probably going to be an improvement.”

“I think he’s been doing this long enough to know where the real problems are,” Kalinowski added. “Whether or not he comes to the exact same solutions I would come to is a different matter.”

Correction: Renée Gentry’s place of work has been corrected in this story.

—

Margaret Manto is a NOTUS reporter and an Allbritton Journalism Institute fellow.

Sign in

Log into your free account with your email. Don’t have one?

Check your email for a one-time code.

We sent a 4-digit code to . Enter the pin to confirm your account.

New code will be available in 1:00

Let’s try this again.

We encountered an error with the passcode sent to . Please reenter your email.