Charlie Dent remembers decades ago when he could campaign in his House district in Pennsylvania without even thinking about security.

Then Gabby Giffords was shot in 2011, a gunman opened fire on Republican members in 2017 and any candidate with a social media account became a target of threats. Dent became used to holding political events with a cop on hand.

“Today it’s only gotten worse,” Dent, who left office in 2018, told NOTUS. “Now these members, they’re worried about going anywhere in public, especially after what happened yesterday.”

The assassination of conservative leader Charlie Kirk on Wednesday was a tragic reminder of how common political violence has become in America. It was the latest in a series of disturbing events that have tested the country’s democratic system of government.

It has also led Republicans and Democrats alike to once again grapple with how this era of violence has already reshaped political campaigns — and how this week’s shooting might change them further.

Strategists in both parties say Kirk’s death hasn’t yet persuaded any candidates to drop out of their race out of concern for their personal safety. But it has renewed a debate over how to better protect candidates while still preserving their access to voters in free and public events.

“A decade ago it was an outlier to hear a recruit ask about personal security or safety. Not unheard of, but rare,” said one Democratic strategist, granted anonymity to speak candidly. “In the last four or five years it’s been more frequent.”

“This cycle,” the strategist continued, “concerns about violence have caused some recruiting conversations to pause, and some to end. Mostly, candidates are being brave because they feel called by concern for their communities and country. But they shouldn’t have to be brave, and there must be others silently selecting out of running.”

A poll of local progressive candidates who ran in 2024 found that nearly a one-third of them had stopped campaigning by themselves because of concerns about personal safety, while one in five said they had either called local law enforcement or installed home security measures because of threats they had faced.

Former candidates and strategists emphasize that candidates on the campaign trail are, in many ways, more vulnerable than members of Congress when they’re in Washington. The Capitol complex has its own police force and well-rehearsed security measures; candidates holding events in their districts or states are often in public venues accessible to many people.

Democratic and Republican officials each say campaign security has evolved significantly in recent years, in part thanks to a decision from the Federal Election Commission to allow candidates to use campaign money to fund protective measures. Candidates who aren’t members work with local and state law enforcement for protection at events, the strategists say, and are encouraged to come up with security measures as part of the everyday operations of their campaigns.

Party leaders say they are thinking of more ways to improve security but aren’t yet making concrete suggestions.

“We’ve asked the sergeant-at-arms for advice on that,” said Rep. Richard Hudson, who chairs the National Republican Congressional Committee. “I don’t have anything new on that, but it’s definitely something we think about.”

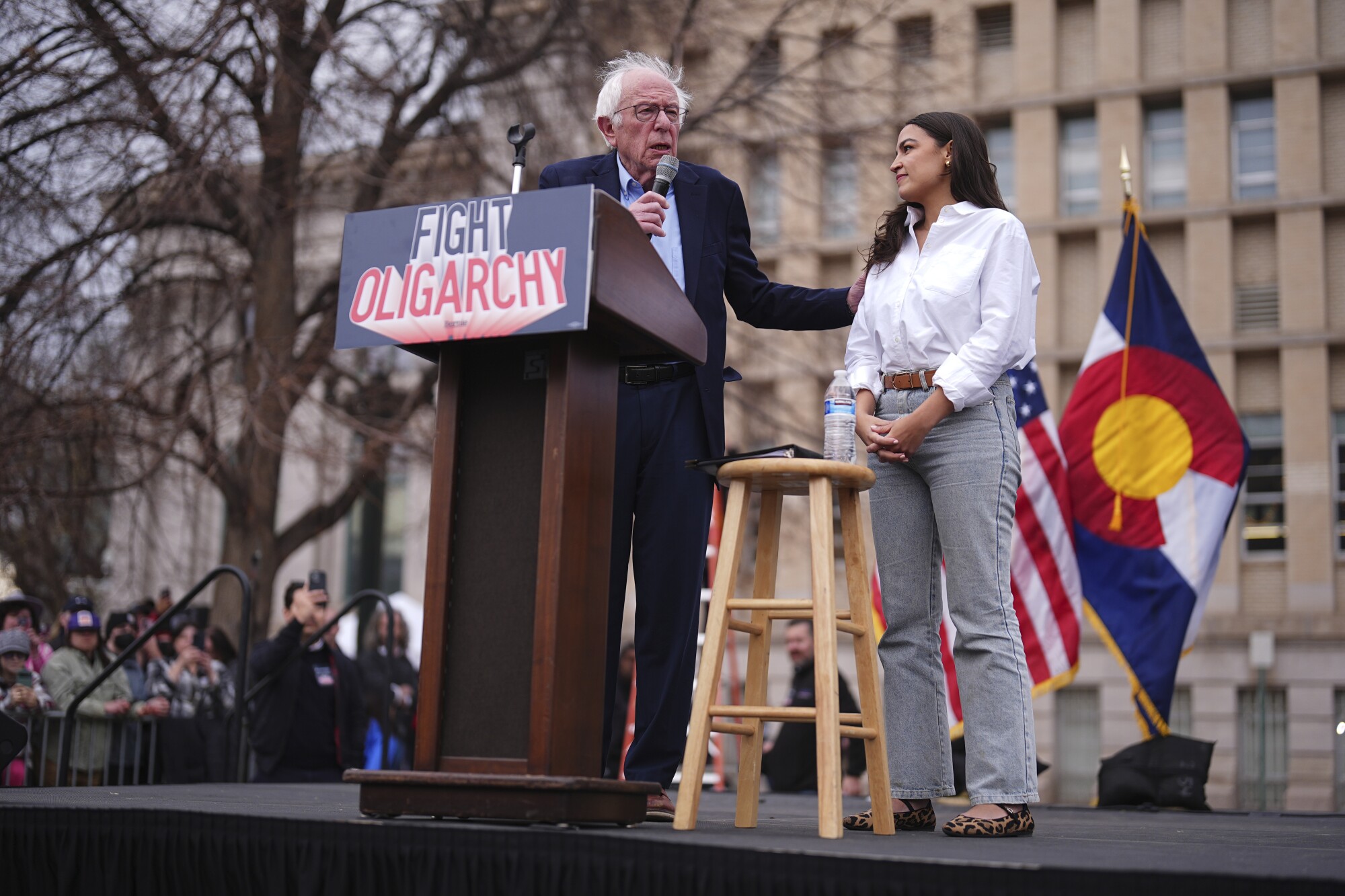

Some politicians, like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, have canceled planned events after Kirk’s death. Not every candidate is doing the same, however: Texas state Rep. James Talarico, a Democrat who announced he was running for U.S. Senate this week, held a political rally as planned on Thursday, although he did change the event’s subject matter.

Strategists involved in campaigns said that for many candidates, as tragic as this week’s developments were, nothing will change. Violence has been a part of political life for many years by now, and many of them are used to it.

“I just feel like people know what they’re signing up for when they run for office,” said one Republican strategist. “Unfortunately that’s just reality, and it’s been going on for a while at this point.”

Dent said his views about security changed in 2011, after Giffords, then a Democratic lawmaker, was shot and nearly died while visiting a local grocery store in her home state of Arizona. Afterward, Dent said he usually had a member of local law enforcement attend whatever event he was holding in his district. Later the congressman also redesigned a congressional office in his district to better protect staff who worked there.

Dent said security intensified again after four people in 2017 were shot attending a Republican congressional baseball game practice, including now-House Majority Leader Steve Scalise.

But after this week’s assasination in Utah, some former elected officials warned about the danger of increasing security further.

Former Rep. Mark Sanford, a Republican who served two stints in the House on both sides of an eight-year-run as governor of South Carolina, said in the past he thought extra law enforcement officials and bodyguards unnecessarily interfered with candidates’ ability to speak directly with voters, leaving them without the person-to-person contact he considers invaluable in a democracy.

Boosting security, or even doing away with public events altogether, only further isolates politicians, he said.

“What’s the trade-off?” Sanford asked. “The tradeoff is you end up with insulated members of Congress, insulated mayors, that aren’t really hearing the direct feedback that they need to hear.”

Sanford said as governor he demanded a slimmed-down security apparatus, sometimes keeping his police detail to a single office. It saved money, he said, and didn’t make him feel any less safe, pointing out that even a small platoon of security officers can’t guarantee a candidate’s safety.

But he also conceded that the current proliferation of threats against elected officials might change one’s calculus.

“In the past, it’s been overdone, overrated, to the taxpayers’ detriment,” Sanford said. “But are we now at a tipping point, and we’re in the new era, and that which was excessive is appropriate now? I don’t know.”

Sign in

Log into your free account with your email. Don’t have one?

Check your email for a one-time code.

We sent a 4-digit code to . Enter the pin to confirm your account.

New code will be available in 1:00

Let’s try this again.

We encountered an error with the passcode sent to . Please reenter your email.