The Influencers: The People Shaping Trump’s New Washington

This story is part of a series exploring the backgrounds and agendas of the players — the well known names and behind-the-scenes operators alike — who will wield power in Trump’s second term.

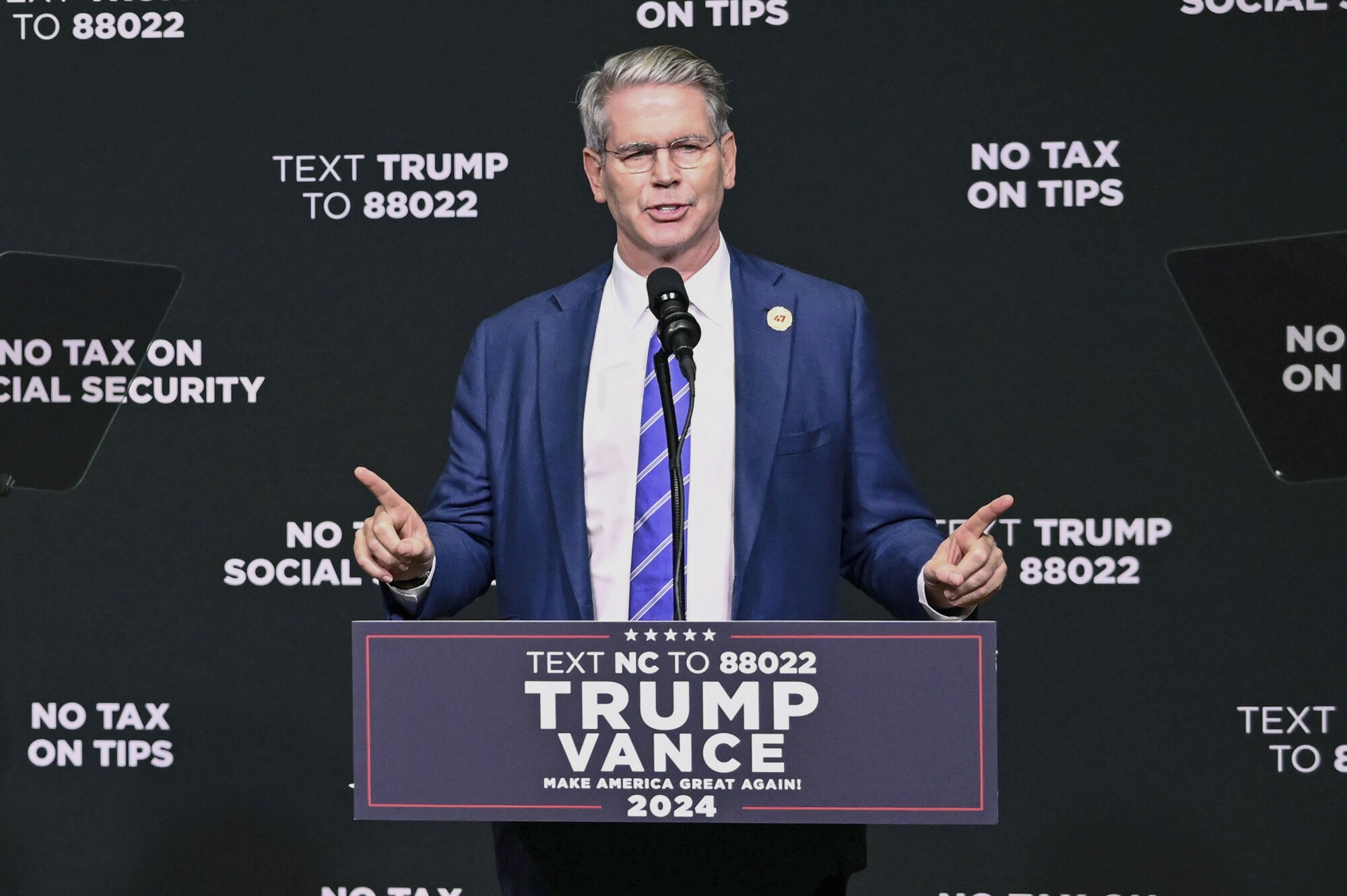

It was June in Washington — five months to go until the election — and Scott Bessent was in full campaign mode. The hedge fund manager was not a household name, even among those who closely followed politics, but was prominent enough in Republican circles to be a featured speaker at a conference hosted by the conservative Manhattan Institute.

During a Q&A with the think tank’s president, Reihan Salam, Bessent explained why he had decided “to come out from behind my desk” to campaign for Donald Trump: Democrats “have a central-planning, top-down mindset,” he said, describing their approach variously as “Bidenomics,” “Bidenflation” and “Biden-itis, ’cause it’s almost like an acute disease.”

He also had some harsh words for the woman he would, in a matter of months, succeed as treasury secretary. In late 2023, Janet Yellen had shifted sales of U.S. debt toward short-term notes and away from long-term bonds. To Bessent, this looked like a cynical ploy to pump quick money into the economy: Yellen, he said in his prepared remarks at the conference, had “departed from norms regarding the issuance profile of Treasury debt in an effort to stimulate markets in advance of the election.”

Fast forward eight months, and Bessent, in his first major move as Trump’s treasury secretary, decided to… maintain the same debt strategy as Yellen.

Hypocrisy? Maybe. Or perhaps it was simply the decision of a most un-Trump-like cabinet secretary: someone who listens, learns and moves carefully. “We’ve already seen an instance where he changed his view, his publicly announced view, based on information and input from advisers,” Wilbur Ross, Trump’s first-term Commerce Secretary and a longtime friend of Bessent, told NOTUS. “I think that’s a very good demonstration of how he’ll go about things. He’s ultimately a very rational, very intellectually fact-driven person.”

It would be difficult to overstate just how strange a fit Bessent (who did not comment for this piece) appears to be in this administration. He’s not a Trump loyalist like Kash Patel; he’s not a middle finger to the D.C. establishment like Tulsi Gabbard or Robert F. Kennedy Jr.; he isn’t a hardcore conservative ideologue like Russell Vought or a product of Trump’s infatuation with media personalities like Pete Hegseth or Dan Bongino.

In an administration full of look-at-me types who relish taunting foreign allies, Democrats and journalists, Bessent’s affect is notably debonair, calm, bookish. “He’s kind of a low-key personality. He’s not a screamer and yeller. He’s not a show-off,” Ross said. “He’s not a lot of things that would interfere with interpersonal relationships. To the contrary, he’s very polite.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, his appointment was opposed by the administration figure most determined to move fast and break things: “Bessent is a business-as-usual choice,” Elon Musk wrote on X before his nomination. “Business-as-usual is driving America bankrupt, so we need change one way or another.”

Bessent is also a longtime employee of George Soros, one of the right’s favorite villains. And in addition to everything else, he is a gay man in an administration that has made opposition to LGBTQ+ rights a centerpiece of its rhetoric and agenda.

It all adds up to a bit of a mystery as to what, exactly, Scott Bessent is doing in this job. And perhaps the biggest mystery of all in the months and years ahead will be whether — and how — he might manage to last.

***

On a breezy Thursday evening in June 1998, an unusual — perhaps unprecedented — scene unfolded in the entryway to Kensington Palace in London: A gay couple was presented to the Prince of Wales. Thirty-five-year-old Scott Bessent and his then-partner, Will Trinkle, were guests at a fundraising dinner for the newly created Prince of Wales Foundation. “It was a big deal to be presented together,” Trinkle recounted years later to royals expert and journalist Sally Bedell Smith. “Those things are preplanned. That doesn’t happen by accident.”

The annual dinners, Bedell Smith explained to NOTUS, “were big ticket items that Scott Bessent could afford.” But, she added, “beyond the money, I think he had a very good and supportive relationship with both” Charles, then Prince of Wales and now king, and Camilla, now queen. (Trinkle did not respond to a request for comment from NOTUS.)

The presentation was notable for another reason too: It symbolized the steep climb Bessent had made during his seven years in London — a period when he was not always well-liked by his British hosts.

Bessent, born and raised in South Carolina, had attended Yale University as an undergraduate. A once aspiring journalist, he nevertheless landed a finance internship one summer and stuck with the field after graduating in 1984. He was sent to London in 1991 by his then-boss, George Soros, to manage European stocks. Within two weeks, Soros had fired everyone else in that office. Bessent, however, stayed on, managing about a third of Quantum Fund’s money, as he recounted in Steven Drobny’s 2006 book, “Inside the House of Money.”

Soon, Soros’s hedge fund hatched a plan that would essentially break the Bank of England. In an incident that came to be known as “Black Wednesday,” the bank was forced to buy sterling back from shareholders at a fixed price, even as the value plummeted. As Sebastian Mallaby chronicled in his 2010 book, “More Money Than God,” Soros amassed more than $10 billion in sterling, shorted the currency and ran off with over $1 billion in profit. (Soros’s Open Society Foundations did not respond to a request for comment from NOTUS.)

Bessent attributed the idea to buy a massive amount of sterling to his colleagues from New York. Yet his role in Quantum’s payday was not insignificant. He realized that mortgages in the U.K., unlike most U.S. mortgages, weren’t fixed rate. The traders knew, Mallaby explained in his book, that when they started selling off their stockpiles of sterling, the currency’s value would drop and the government would be forced to raise interest rates to lure back investment. But Bessent flagged to Soros in the planning stages that the government was limited in its ability to use this economic salve because raising interest rates would hit nearly every homeowner in the country.

“They basically squeezed everyone in the United Kingdom with a mortgage,” Bessent told Drobny. “When they raised rates from 7 percent to 12 percent with the stated goal of defending the pound, we knew it was unsustainable and that they were finished.”

It was, Ross told NOTUS, “probably the single most successful trade that Soros and maybe anybody else ever made” — and it did not make Bessent a popular man in London. “After that, a lot of companies wouldn’t meet with me. At first, it was a matter of national pride for the Brits,” Bessent told Drobny. “But as they saw interest rates come down and the economy improving, they softened their stance.”

By the time Bessent left London in 2000, “obviously they really accepted him,” Bedell Smith said, noting that he lived at Albany, a storied British complex housing the London elite — “which was not an easy thing for an American.” Somehow, Bessent had managed to burnish his reputation while operating in the shadow of a chaos-causing, headline-hogging boss.

When he returned to the United States, he started his own firm — which, as The New York Times reported late last year, had mixed success — then shuttered it within five years. By 2012, he was back working for Soros again — and that year, in New Haven, he had a conversation about Japan’s economy that he later described, in a piece he wrote for The International Economy, as a “day I’ll never forget.”

Huddled among the athletic trophies and Yale pennants adorning the wood-paneled walls of Mory’s — a private club and restaurant near his alma mater — were Bessent, Soros, a colleague and Koichi Hamada, an economic adviser to soon-to-be reelected Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe. The four were discussing Abe’s economic plan, also known as the “Three Arrows.”

It was the start of what Bessent would describe as “the Bank of Japan’s fantastical decade of ultra-loose monetary policy” — a political plan to drive investment that Bessent later plotted to cash in on. “I’m not sure whether [Abe’s plan] will work, but it will be the market ride of a lifetime,” Bessent told Soros.

Months after that lunch, Bessent, now the chief investment officer of Soros’s fund, bet against the Japanese yen. Forbes called the move — which would prove to be successful, though not nearly as successful as the London affair — “vintage Soros.”

Hamada, the Abe adviser from the lunch that got the investment wheels turning, told NOTUS he had forgotten Bessent was even there. But he did remember subsequently meeting him in New York. He contrasted Bessent’s demeanor with that of Soros, who tossed bold policy ideas his way. Bessent, Hamada recalled, was a “very good listener” and “not forthcoming with policy or ideas.”

Hamada isn’t the only person to characterize Bessent as having an air of reticence. A longtime colleague, Gary Gladstein, described him as “reserved,” though, at the same time, not entirely averse to public life. “I think Scott enjoys getting some publicity,” Gladstein told NOTUS.

“I would call him a reluctant society figure,” R. Couri Hay, a New York publicist who crossed paths with Bessent at various elite parties over the years, told NOTUS. “He’s not competitive for the camera. He’s not competitive for the press attention.” He has, it would seem, a more modest disposition than many of his new colleagues in the administration — which may prove to be an asset when seeking to survive the upheavals of Trump’s Washington.

***

“For 35 years, I’ve been sitting outside the room with my ear up against the door,” Bessent told Bloomberg recently. “Trying to figure out what policymakers should do or are going to do and how that would affect markets. Now I’m inside the room trying to figure out what everybody outside the room expects us to do, how the market’s gonna react.”

For most of his career, Bessent has not had much of a public political profile — “I didn’t see him as a political person,” Gladstein told NOTUS — but he didn’t exactly ignore politics either. He made small donations to Mitch McConnell in 1996 and Hillary Clinton in 1999 for their respective Senate races, then gave more than $100,000 to a Democratic National Committee-affiliated account in 2000. In 2007 he donated to Barack Obama, and in 2008 to John McCain. In 2013, he gave $25,000 to a PAC that was paving the way for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign. The balance of donations to Democrats versus Republicans had shifted to the right by the time of Trump’s first campaign, and over the past decade he’s become a major GOP donor — giving more than $1.3 million to the Republican National Committee since 2017, and well over a million to Trump-affiliated PACs this cycle.

As a veteran of the world of finance tossing around massive campaign contributions to get Trump elected, Bessent was never going to be well-received by progressives: Speaking to NOTUS, Sen. Elizabeth Warren denounced “all of his work to squeeze extra money out of every rule or trick or path in order to help rich people and leave everyone else behind.” But the installation at the Treasury Department of a Wall Streeter with a bipartisan, centrist track record did appear, at least at first, to fit a conventional pattern stretching back decades — one that included Trump’s first-term treasury secretary.

Bessent is “very, very knowledgeable. Reminded me in some ways of Steven Mnuchin,” Sen. James Lankford, who sits on the Senate Finance Committee, told NOTUS. Both men “could go right through to be able to talk through policy areas.”

Mnuchin brought a certain sense of stability to the first Trump administration. He maintained professional processes at Treasury and negotiated closely with Nancy Pelosi. He was, as Business Insider recently explained, “the guy who reassured markets everything was going to be all right.”

Almost two months into his tenure, it’s far from clear that Bessent will do the same. The trouble started soon after Bessent’s confirmation, when Musk and the Department of Government Efficiency began accessing Treasury’s systems. In an interview in early February with Bloomberg TV, Bessent attempted to reassure viewers that DOGE’s role at Treasury was limited. “There is no tinkering with the system. They are on ‘read-only,’ they are looking, they can make no changes. It is an operational program to suggest improvements,” Bessent said. Around the same time, according to Politico, he provided similar reassurances to Congress.

However, after Wired reported otherwise and new court records showed that the DOGE team had broader access to payment systems than past auditors, Senate Democrats were furious: “It is highly concerning that you are either misrepresenting basic facts to Congress and the American people — or simply do not know what DOGE is doing in your agency,” they wrote to him. (A deputy inspector general at Treasury later told lawmakers they had launched an audit, writing that “we recognize the danger that improper access or inadequate controls can pose to the integrity of sensitive payment systems.”)

Graham Steele, an assistant secretary under Yellen, told NOTUS that the entire episode was “a real early hit to his credibility about what kind of secretary he was going to be and what kind of principles and values he was going to stand up for. If you had asked me before that what he was going to be like, I was hearing … ‘This is gonna be somebody coming from finance, similar to Secretary Mnuchin, not gonna be that different.’ Those early steps were really a problematic signal about how much independence there really was going to be at Treasury.”

Then, as markets began to fall in early March — fueled by uncertainty surrounding Trump’s tariff threats — Bessent went on CNBC and defended the instability as part of a “detox period” (though he later told NBC that “we are not going to have a crisis”). He also said, during a speech at The Economic Club of New York, that cheap goods are “not the essence of the American Dream.”

In making bold proclamations, Bessent seemed to be displaying the public ideological loyalty that his boss wants. “Trump likes there to be initial disagreement among staff people. He would call a bunch of us into the Oval on some issue or another and he’d like to hear everybody out. But once he felt he had heard enough to make his decision, that would be the end of the discussion,” Ross said. “Scott will be very much of that mind. So I think to the degree that they have disagreements, it will be in the Oval or in an office. It won’t be in the media.”

The problem is that Bessent’s job requires him to project not just loyalty but also stability — and that may lead to inherent tension with a president whose governing style provokes constant chaos. “Scott is a terrific guy. Whether he can stand up to the president or not — I don’t know,” Gladstein said.

David Smick, a colleague during Bessent’s early years working for Soros, put it this way to NOTUS: “I think Scott, because he’s careful in what he says and it’s not just flying off the handle — ’cause he’s obviously different from a lot of the crowd there — I think that’s gonna serve them long-term in a positive way. They’re gonna say he’s a steady hand, the calm in the storm, the calm voice.” Indeed, his mild demeanor, his history of working effectively behind the scenes, his track record of surviving financial mayhem, his apparent willingness to listen and adapt — all of these traits could be exactly what the Trump administration needs to get along with Wall Street over the next four years. If, that is, Scott Bessent has a chance to use them.

—

Claire Heddles is a NOTUS reporter and an Allbritton Journalism Institute fellow.

Sign in

Log into your free account with your email. Don’t have one?

Check your email for a one-time code.

We sent a 4-digit code to . Enter the pin to confirm your account.

New code will be available in 1:00

Let’s try this again.

We encountered an error with the passcode sent to . Please reenter your email.