Ron DeSantis suspended his campaign on Sunday afternoon ahead of what was expected to be a lackluster showing in New Hampshire. “It’s clear to me that a majority of Republican primary voters want to give Donald Trump another chance,” he said in a video on X.

Read more from Friday on why DeSantis’ campaign fell short:

WEST DES MOINES, Iowa — Two days before coming in a distant second place in the Iowa caucuses, Ron DeSantis took the stage in his campaign’s West Des Moines headquarters to make a final pitch to the voters he had spent the last year courting. Within the first three minutes of his speech, he had already cited Anthony Fauci’s COVID-19 policy, his efforts to ban Chinese citizens from buying land in Florida, school choice policy and teachers unions, his war with Disney over LGBTQ+ rights, George Soros and “ballot harvesting.”

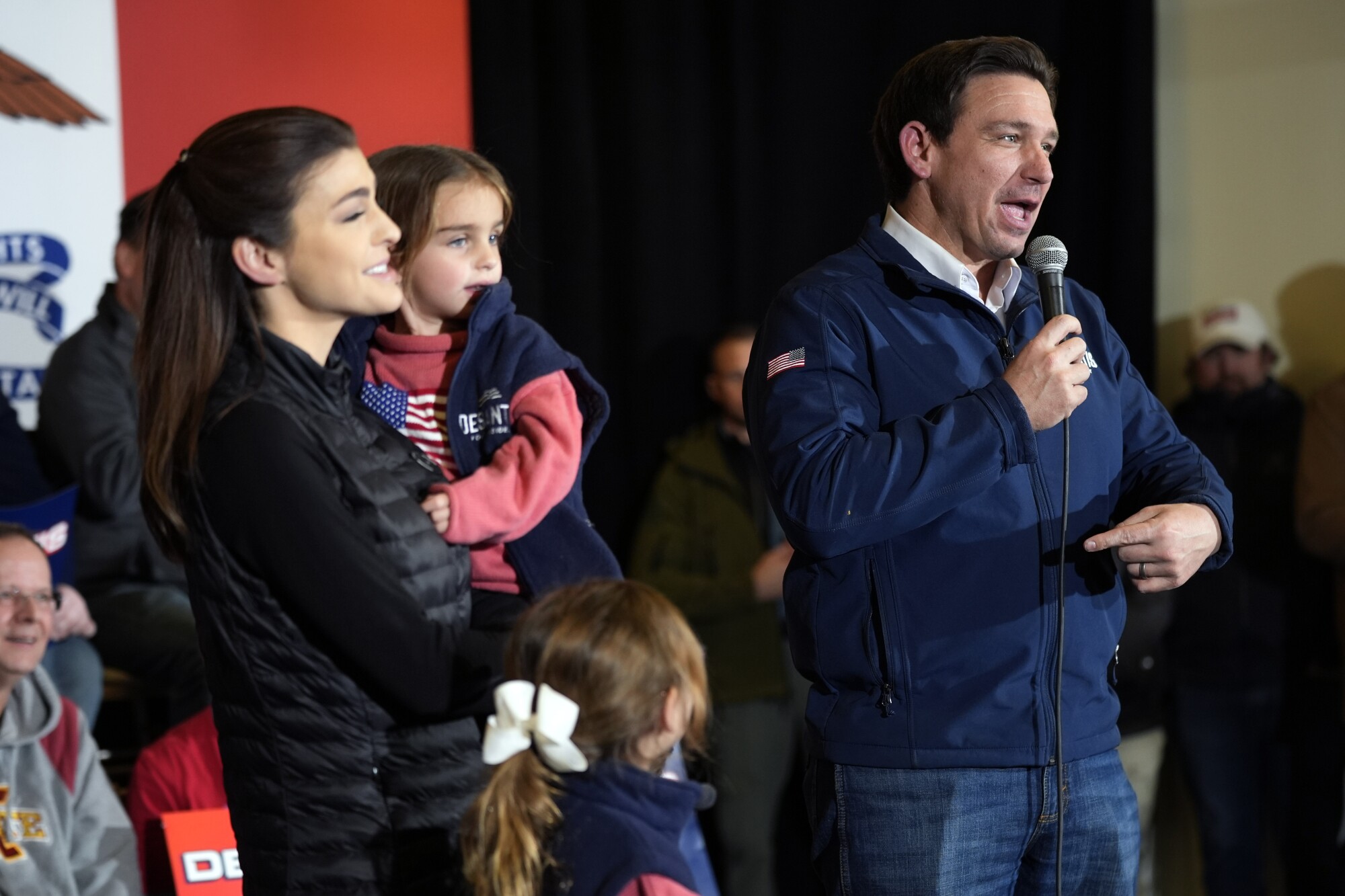

Karen DeSantis, the Florida governor’s mother, was sitting in the crowd, but he didn’t mention her. Nor did he talk about Casey DeSantis, his wife, who was poised next to him on stage holding their son, Mason, in those opening minutes.

Eventually, he did arrive at a quick story about Mason rooting for Iowa in a football game, a segue to talking about the future of America for kids, before pivoting to veterans issues — an issue his campaign has laid out an acronym-filled plan to rollback “CRT, DEI, paid leave/travel for abortion” and other policies.

DeSantis’ result in Iowa gave his campaign enough energy to continue to New Hampshire but still raised doubts about its long-term viability. In the days that followed, Never Back Down, the super PAC supporting his candidacy, announced layoffs. DeSantis himself is set to spend as much time campaigning in South Carolina, whose primary is next month, as he is in New Hampshire.

Now, with his campaign flagging and bracing for an even worse showing in New Hampshire, DeSantis’ detail-heavy style is being blamed — at least partially — for turning his front-running candidacy into a political also-ran. Without a quick turnaround, DeSantis looks ready to join a long list of recent presidential candidates who made a misguided attempt to overemphasize policy over the personal.

“He seems to like governing,” said Henry Olsen, a senior fellow at the conservative Ethics and Public Policy Center. “He doesn’t seem to understand how to campaign.”

Since launching his bid for the White House, DeSantis has maintained an almost single-minded focus on niche conservative policy on the campaign trail. He’s deep in the culture wars that he hoped would animate the Republican base, but it’s a culture war by way of PowerPoint presentation, going point-by-point through an exhaustive account of his gubernatorial record and a detailed pledge of what he would do as president. He has a 1,400-word denunciation of China — addressing things like “post-quantum encryption standards” — under the first policy priority on his campaign website.

That type of approach, which showed no sign of dissipating as he hit the campaign trail in New Hampshire this week, is especially conspicuous in a GOP primary against rivals Donald Trump and Nikki Haley, both of whom make their life stories and personal feelings the center of their campaigns.

DeSantis’ allies and friends say it is a deliberate style that mirrors the Florida governor in private settings: a research-intensive wonk who, even among friends, is often more interested in debating public policy than swapping personal stories. DeSantis’ campaign, to some success, even designed a strategy to win key local endorsements around his interest in niche issues, often deliberately putting him in a room with groups of state lawmakers from Iowa and New Hampshire to let the governor help them troubleshoot policy problems based on his own experience in Florida.

“I don’t know that he’s fully come to terms with the fact that if you’re running for president, voters want to know who you are,” said former GOP Rep. Carlos Curbelo of Florida, who has not endorsed anyone in the presidential primary. “They want to get to know you, they want you to open up and bare whatever’s on your mind beyond your position on the issues.”

Even though the two men had a good relationship during the four years they served in Congress together, Curbelo said he knew next to nothing about his then-colleague’s family life or upbringing, despite the two men seeing each other almost every day.

“More than a wonk, he was just focused almost exclusively on his policy and personal political objectives,” said the former lawmaker.

Voters, too, even those who attended his rallies in Iowa, often leave ignorant of key facts about the governor’s life. That biographical deficit is especially concerning to some DeSantis supporters, who point out that the Republican politician’s faith — he’s a church-going Catholic — and background — he grew up in a working-class family near Tampa — should be major selling points of his candidacy.

Striking a balance between personal anecdotes and policy explanations is often a delicate task on the campaign trail. Talk too little about policy, and a candidate can look like a lightweight out of touch with what matters most to some voters. Geek out too much, however, and run the risk of becoming a candidate like Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) or Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah), more at ease talking about white papers than their own lives.

“I hope voters are voting for policy and not based on their perception of how much they might desire to have a beer with someone,” said Jason Osborne, the state House GOP majority leader in New Hampshire who endorsed DeSantis after the governor held one of his policy-heavy meet-and-greets. “But I certainly fear that might not be the case.”

It’s not as if DeSantis never mentions his family or upbringing, although the style in which he talks about them can often feel like an exercise in box-checking. He tells stories about playing baseball with his son (DeSantis played on Yale University’s baseball team) and mentions Iowa landmarks he toured with his family. He references his military service in the U.S. Navy. And when really pressed in interviews about personal matters, as happened earlier this month when CNN’s Kaitlan Collins asked about his late sister, he can answer forthrightly.

But even friends concede DeSantis likes to talk more about policy specifics than even most obsessives in politics. In the weeks before he launched his campaign in May, the governor gathered a roundtable of political allies like Rep. Thomas Massie of Kentucky, not to talk about his path to victory in the Republican presidential primary, but to have a day-long conversation about 16 different subjects. On the campaign trail, half of his stump speech could be dedicated to a comprehensive recitation of his record as governor, usually including even relatively minor points like his dismissal of a local prosecutor in Florida or opposing a vaccine mandate for the Special Olympics. The governor turned culture war topics into specific policy proposals, touting his plan to grant sales-tax exemptions for gas stoves or to remove the Walt Disney Corp.’s special state tax status.

“That’s clearly what he likes to talk about,” said Justin Sayfie, a Republican lobbyist in Florida. “And that’s clearly his strength.”

Sayfie said he didn’t think that focus hurt DeSantis. Others working on DeSantis’ behalf, however, aren’t so sure, a skepticism that has only grown since the governor lost Iowa by roughly 30 points to Trump.

“He’s such a talented political figure with an incredibly compelling background,” said one GOP official who worked to elect DeSantis and to which NOTUS granted anonymity so that he would speak candidly. “And I don’t know that he’s done a great job communicating that. But more importantly, I don’t know that those who worked for him have done a great job doing that, either.”

Some DeSantis supporters say they’re frustrated that efforts made earlier in the race to define him as a blue-collar alternative to Donald Trump — an early ad from the DeSantis-supporting Never Back Down called DeSantis the grandson of a steelworker, and the candidate himself used to mention in his stump speech how he had to earn everything in his life — never saw follow-through.

That might be partially a consequence of the success DeSantis had in prior campaigns in Florida, they added, where he twice won statewide gubernatorial elections in races where policy red-meat was all some voters wanted. A presidential run, however, they say, requires a whole different level of engagement with the electorate.

Back in the West Des Moines office building housing Never Back Down’s Iowa headquarters, even the voters that trekked through blizzard conditions to see him didn’t seem to know much about another politically important part of DeSantis’ life – his faith. “I’ve heard him saying he’s Christian on some level, but I really couldn’t say,” said Char Wade, a then-undecided caucus-goer. At the time she was leaning either toward DeSantis or Vivek Ramaswamy, both of whom she saw as strong on “pro-life” issues. Wade ended up caucusing for Ramaswamy.

For his part, Ramaswamy told voters at a rally in Ames on Sunday, “I believe there is one true God and he put us here for a purpose.” During DeSantis’ stump speech on Saturday, the only mention of his faith was his final two words: “God bless.”

That aversion to speaking about his religious beliefs goes back to the very beginning of DeSantis’ campaign in Iowa: During his May campaign kick-off rally in West Des Moines, the Florida governor barely mentioned God or talked about his own faith — despite holding the event in a church. Osborne and another DeSantis supporter, former Rep. Keith Rothfus of Pennsylvania, say they’ve each personally seen the governor attend church with his family in New Hampshire and Iowa, respectively, but declined to notify local media in order to keep the services private.

“There’s a private side to people,” said Rothfus, who is the godfather of DeSantis’ eldest daughter and attended one of the private church services with his former congressional colleague this year.

When NOTUS began asking the former Pennsylvania lawmaker why he thought the governor was so focused on public policy instead of his personal life, he interrupted the question halfway through. “Because we’re trying to explain how to fix the country!” Rothfus said. “Forget these little anecdotes.”

Rothfus, like other DeSantis supporters, describes the governor as a politician so bent on sharing how he plans to change the country that he often doesn’t consider any other rhetoric worth his time. That mindset might have proven unpopular among Republican voters on Monday, but the candidate’s allies say it’s a foundational part of DeSantis’ personality.

“It’s probably because he doesn’t care about that, right?” Osborne said. “Why does it matter whether someone comes from a certain background or not?”

DeSantis caucus captain Lance Lillibridge, said it’s exactly that policy obsession driving his support for DeSantis. “I’m a farmer and policy and agriculture is a big deal, and so to be able to have a conversation with the candidates and try to get where they’re at on a policy position on things is super important to me. DeSantis is the only one that’s checking all the boxes,” Lillibridge said. “He’s got a team of people that are actually working on policy. … I think his team has asked me more questions than I’ve asked him.”

But many voters aren’t like Lillibridge. Olsen, the senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, said politicians often fall into one of two camps: workhorses, who understand deeply the policies they work on but have little public presence, and showhorses, who have only cursory knowledge of policy but play well with voters. DeSantis appears to be the former, Olsen said.

“What is interesting is those people tend not to run for president. When they do, they always lose,” the think-tank fellow said. “What voters are looking for is a person and vision for the future.”

DeSantis’ emphasis on his conservative plans for the country, of course, isn’t the only reason his campaign has fizzled. At times, it’s been the policies themselves; DeSantis’ embrace of a series of far-reaching policy positions, including signing a six-week abortion ban in Florida, alienated some Republicans who had hoped he would be a more moderate candidate. And, his campaign’s relationship to Never Back Down has been a well-publicized mess. Trump, as Monday’s results show once again, also retains a unique hold on GOP voters, one that multiple indictments last year seemed only to strengthen.

In New Hampshire, however, DeSantis’ allies continued to sell the governor to voters by pointing to his policy acumen. Massie, speaking Wednesday, touted DeSantis’ deep knowledge and defense of the Second Amendment — he wouldn’t ban so-called bump stocks for rifles, for example — and touted how the Florida Republican, while a congressman, was more interested in talking about policy than the Washington social scene.

“We didn’t put on tuxedos and go to the champagne parties like all the other congressmen,” Massie said. “We’d go eat a hamburger and talk about the bills we had to vote on the next day. We thought that was our job. This is a guy who takes his job very seriously.”

Voters in Iowa appeared to understand DeSantis took his job seriously — some of them just didn’t know much more about him than that. His personal connection to voters might be even weaker in New Hampshire and South Carolina, where DeSantis has spent less time.

On the Saturday before the Iowa caucus, DeSantis supporter Scott Bates, sporting a “Dads Against Daughters Dating Democrats” shirt, said he put in the extra effort to get to know a fuller picture of the candidate. He’d read both of his books (he even had one in his pocket), attended multiple rallies and even met DeSantis’ mom — saying she reminded him of his late mother.

But those personal details that Bates identified with weren’t anywhere in DeSantis’ speech that day — and most attendees would never come to know that his mother was in the room. DeSantis used the word “family” twice in his speech, both directed to the audience: “I’m running on your family’s issues,” he said at one point, and, “Bring some family members” with you to the caucus, he said at another. Mention of his own family, however, hardly made the cut.

—

Alex Roarty is a reporter at NOTUS. Claire Heddles is a NOTUS reporter and an Allbritton Journalism Institute fellow.

Sign in

Log into your free account with your email. Don’t have one?

Check your email for a one-time code.

We sent a 4-digit code to . Enter the pin to confirm your account.

New code will be available in 1:00

Let’s try this again.

We encountered an error with the passcode sent to . Please reenter your email.